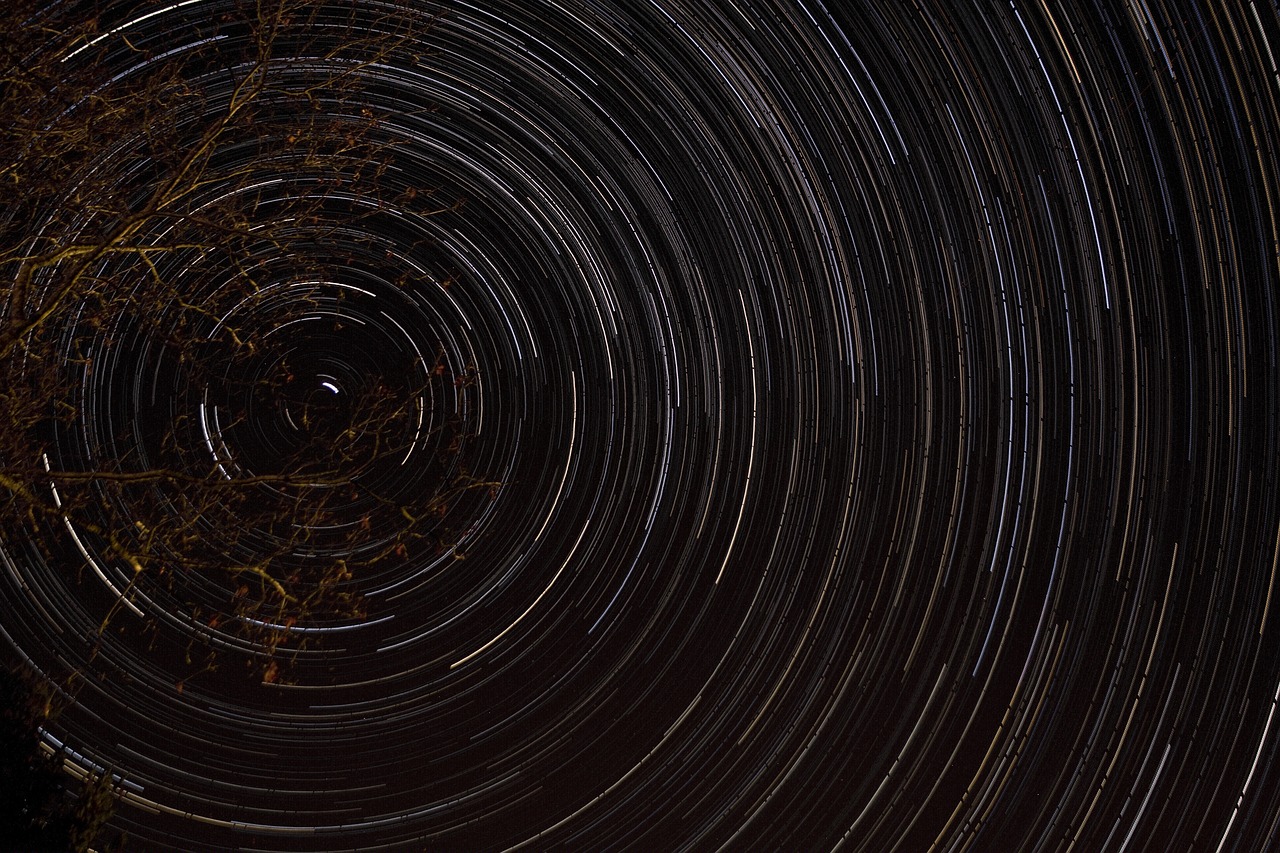

In the northern hemisphere, certain constellations appear to rotate around the north star. These constellations are called the circumpolar constellations because they stay above the horizon all night long, even as the other constellations rise and set in the night sky. The most obvious circumpolar constellation is Ursa Major or the Big Dipper. If you look closely at this constellation, you can see that it has two parts: a cup shaped part made up of four stars and three pointer stars that are almost directly above Polaris, also known as the north star.

Constellation Mythology

In Greek mythology, Orion was a handsome young hunter and son of Poseidon. He was born at a time when Gaia, or Mother Earth, was mourning for her dead lover and son Dionysus. To cheer her up, Helios (the Sun) sent Eos (the Dawn) to wake her with some new gossip – she tells Gaia about Orion’s dalliances with many beautiful water nymphs. Enraged, Gaia asks Artemis and Apollo to kill him. They kill him by shooting him with arrows while he is sleeping. His faithful hunting dogs try to revive him but fail; Zeus then transforms them into stars so they can be close to their master forever in death as they were in life. In other versions of the story, Artemis kills Orion herself by accident while trying to protect her virginity from his amorous advances. The constellation takes its name from either Orion or Oeneus, who was King of Calydon in Aetolia. When Oeneus forgot to honour Artemis at an important religious festival, she punished him by sending a ferocious boar across his lands that killed both men and animals until it was eventually killed by Meleager. Oeneus’s wife Althaea threw a log on to the fire in revenge which revived and transformed into a wild pig which immediately killed her sons. She then took her own life. However, Artemis turned them all into stars so that they could be together again – Althaea became Capella (the leader of Auriga), Meleager became Corona Borealis, one of Orion’s hunting dogs became Sirius, another became Procyon and one of Oeneus’ sons became Betelgeuse.

The Big Dipper and Little Dipper

The most recognizable constellation in northern skies is Ursus Minor, more commonly known as The Little Dipper.The Big Dipper is a constellation composed of seven stars (which all have official names) and is located roughly half way between Polaris and Alpha Draconis, which you can also know as Thuban. It’s easy to find because it looks like a big ladle or dipper. It’s part of an asterism called The Plough or Charles’ Wain that includes several other stars. You could say it’s part of Cygnus, but I prefer not to split hairs about what constitutes an asterism versus a constellation. You may notice that there are only six stars in The Big Dipper instead of seven. That’s because one of them has gone supernova! Supernovae are extremely bright explosions caused when a massive star dies. A supernova explosion occurs when a giant star uses up its fuel supply and collapses under its own gravity, creating an extremely dense object called a neutron star or black hole. A supernova releases huge amounts of energy, often enough to outshine entire galaxies. In fact, if you were close enough to see a supernova go off right now, it would be brighter than every other star in our galaxy combined! When we look at The Big Dipper today we see that one of its stars no longer exists on Earth—but astronomers thousands of years from now will still be able to see evidence of its existence.

The North Star

The most famous of these is Polaris, or the North Star. Contrary to popular belief, however, it is not stationary. Instead it moves in a small circle with a radius of about 2° per year. For example, if you observe Polaris from Boston in February 2013, you will note that it has drifted about 1° westward relative to its position three months earlier. This motion is due to two factors: precession and proper motion. Precession refers to a gradual shift in an object’s direction caused by gravitational forces acting on it over time. In Earth’s case, we are talking about forces exerted by our planet’s moon and sun as they orbit Earth. Over thousands of years, these slight shifts add up. As for proper motion, all stars move through space at varying speeds depending on their distance from us. Polaris happens to be one of our closest neighbors (it is only 434 light-years away), so it travels more than twice as fast as other stars—more than 20′′ per century! It will take another 4200 years before Polaris returns to its current position in space. But don’t worry; there are plenty of other bright stars nearby!

Special Cases

Circumpolar stars are ones that stay above a point in space, while all other stars move below. The North Star is one of these special cases, as it never sets in our sky, but also doesn’t rise or fall, as other stars do. Instead, it appears to stay perfectly still directly over Earth’s North Pole — hence its name! It does have some company up there though; for example Draco (The Dragon) lies coiled about half way between Polaris and The Big Dipper. Another interesting fact: if you were to travel far enough south, all of these circumpolar constellations would eventually disappear from your night sky. That’s because their declination is greater than your latitude! For instance, at 40 degrees north latitude, only circumpolar constellations like Ursa Major will be visible. At 50 degrees north latitude, only Ursa Minor will be visible; at 60 degrees north latitude, both can be seen together with no others visible at all! If you go farther south than 60 degrees north latitude – say down to 30 degrees – then neither constellation can be seen from your location. So what happens when we go even farther south? Let’s take a look at how different locations on Earth view these two constellations, starting with New York City. Here, Ursa Minor is just peeking over the horizon; let’s see how things change as we head westward toward San Francisco. By San Francisco, Ursa Minor has risen higher into our sky and now dominates it.

![]()